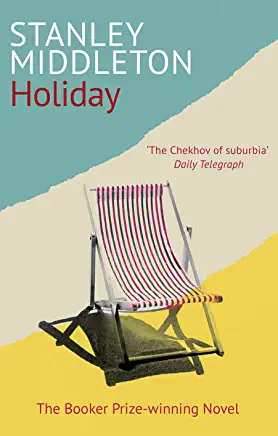

According

to Wikipedia, Middleton was a creative powerhouse – he was a talented church

organist and a gifted water-colourist too. He wrote 45 novels, twelve of them

before he wrote Holiday. His first novel was published in 1958, the last

one in 2010 (a year after his death). He was an English teacher at High

Pavement Grammar School in Nottingham for many years. And apparently he turned

down an OBE due to believing he shouldn’t be rewarded for doing what he saw as

simply his job *.

I have

never read Holiday but it was clearly sufficiently accomplished to be

awarded a prestigious literary prize. This was a man of great ability, a man

whose literary life was, by most people’s standards, a successful one. Yet I

have never heard of him or his most famous novel, and neither have any of the

people I have asked.

I tell

you this because it has made me think long and hard about this weird activity

in which we engage our energies, we writers.

For most of us, whether we are any good or not, and even successful and

talented people like Middleton, it is an unrewarding activity, at least in

terms of the way most people judge ‘rewards’. Middleton was able to publish his

novels, win a Booker and be offered an OBE, but he presumably never achieved

the wealth or fame of the handful of contemporary novelists most people have

heard of – J.K.Rowling, Robert Harris, Terry Pratchett, etc. Now, around a

decade after his death, I suspect that he is generally forgotten, except by

those who knew him and those who know his books. Who knows? His reputation

might be revitalised in years to come – there have been many creative artists

in different fields who were quickly forgotten after their deaths but later

‘rediscovered’. But, for now, Middleton seems to be a relatively forgotten

author, despite his success during his lifetime.

Writers

like myself, who have had some things published but nothing that has made them

any money or given them any fame, would love to achieve Middleton’s success.

Forty-five published novels! A Booker Prize! An OBE! Yet most people I speak to

who aren’t writers and readers (and that is, in fact, most people) would

consider such success to be relatively unimpressive. More obvious worldly

achievement is generally better-respected these days (and perhaps always has

been) – massive wealth, a name and a face that everyone recognises, books that

top the bestseller lists, novels that are picked up by Hollywood and made into

movies. There are novelists who have these things even though they are dreadful

writers and will probably be forgotten forever after their deaths. There are also,

of course, extremely talented writers in this category of the super-successful

who will be remembered fondly for many years by many people. But, in today’s

publishing world, achieving Middleton’s level of quiet success is a major feat

in itself – hell, getting a novel published in the first place is like winning

the lottery, and having further novels published if your first one isn’t as

successful as your publishers hoped is virtually an impossibility.

In 2006,

The Times pulled a stunt that produced some interesting results. They

circulated the first chapters of Holiday, and also of a novel by

V.S.Naipaul, to numerous agents and publishing houses, presumably using false

names. All rejected Naipaul’s novel, and only one agent accepted

Middleton’s. From this, we can assume

that publishers in the twenty-first century have different tastes, or know that

their readers have different tastes, or are simply unwilling to invest in

‘literary’ novels.

What

lessons can we learn from this? Do we give up writing? Is it a pointless waste

of time? I have two thoughts. One is

that, if you are a writer, you can’t stop yourself writing – writing is your

greatest pleasure (which isn’t to suggest that it isn’t often difficult,

painful and stressful) and a writer is who you are, published or not. Earning

your living through writing is another thing entirely. The second is that we

need to see the rewards of writing, just as we see the rewards of reading, as being

different in kind from the rewards of, say, being a solicitor, or a surgeon, or

Kim Kardashian, or the founder of Google or Amazon. The rewards are intrinsic,

not instrumental. There is something inexpressible that every writer who is

serious about their craft has experienced – a feeling of satisfaction in having

successfully translated what existed inside your head into something that

others can understand if they want to. It is nice if people read what you have

written, even nicer if they enjoy it – nicer still if they take the time to

tell you they enjoyed it – but, even if no one ever reads it, you still have

that profound sense of having achieved something worthwhile, however flawed you

feel it is.

The joy

of becoming better at something you find intrinsically enjoyable is in itself

one of the rewards of taking yourself seriously as a writer. And I’m not even

mentioning the myriad rewards of the actual writing itself – the pleasure to be

had from putting the best words in the best order, of exploring new worlds,

constructing lives, creating characters, getting inside their heads, telling their

stories, examining ideas and philosophies and what ifs. The act of attempting

to entertain others is profoundly enjoyable. There is a therapeutic quality to

writing at times – self-expression, creative contentment – and sometimes a

performative element too, a showing off. Few writers are rich and famous, and

in fact many barely make a living at all from their writing. Many never give up

the day job. But no one would do this activity, which is hard and

time-consuming and exhausting, if they didn’t get some sort of deep-seated

intrinsic reward.

Some of

us might manage to write the novels or stories or poems or scripts that fill our

imaginations. Being published, read, performed, admired, or paid – well, that’s

the icing on the cake. The sad fact is that most of us are lucky to get even

the cake, but sometimes it’s enough just to smell the batter rising in the oven...

* https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stanley_Middleton

No comments:

Post a Comment